FiveThirtyEight is wrong

Nate Silver and Harry Enten claim The System Isn’t ‘Rigged’ Against Sanders. I’ve written at length already debunking their argument and drawing attention to the statistical malpractice they rely on to make it. To summarize, their argument is that caucuses have favored Sanders by suppressing the vote, and that somehow this disadvantages Clinton supporters more than Sanders supporters. Using a severely flawed statistical model they estimate that Clinton would have done 20-25% better in caucus states if they held primaries instead. To their credit, Silver and Enten attempted to address the question of having open vs closed primaries. But despite the sweeping title of their article (the system!), their focus is entirely too narrow. They identified two possible mechanisms by which the system could be influencing votes: caucuses vs primaries and whether or not the vote is open to independents.

The system IS rigged against Sanders

I conducted my own analysis to address some problems with theirs. Their model included percent of population that is black, percent Hispanic, whether the vote was a primary or caucus, whether it was open or closed to independents, and the national polling margin at the time of the vote. I’ll do several things slightly differently. Instead of national polling margin, I’ll just use the date–this is highly correlated with the national polling margin anyway. I did this more out of convenience than anything else, because my data already had date but not national polls. This difference is not important. Next, I’ll include just one more variable: whether or not the state has same-day registration. It just so happens that almost every caucus state also has same-day registration. Here are the coefficients of the resulting model:

| Variable | Estimate | Std. Err. | p-value |

| (Intercept) | 69.2271 | 4.2055 | <0.00 |

| Date | 7.5544 | 7.1372 | 0.3 |

| Deadline | -5.6614 | 5.1451 | 0.28 |

| Type | -5.946 | 5.2812 | 0.27 |

| Independents | 2.232 | 2.7884 | 0.43 |

| RaceBlack | -1.1415 | 0.1488 | <0.00 |

| RaceHispanic | -0.3431 | 0.1974 | 0.09 |

Let me break this down for you. Ignore the (Intercept) variable. The Date variable estimate of roughly 7.5 means that, on average, Sanders has gained 7.5% comparing the most recent votes to the first votes early on. The Deadline variable at about -5.7 means Sanders loses about 5.7% on average when states do not allow same-day registration. The Type variable means Sanders loses 5.9% in primaries compared to caucuses, again on average. (As an aside, if I leave out Deadline and have almost the same model as 538, the Type variable estimate is about -10.46, still not quite the absurd estimate Silver and Enten present). The Std. Err. and p-value columns tell us roughly how certain we can be that the estimate is good and that the effect isn’t really just zero. Many of the p-values are above the traditional 0.05 “significance” cutoff because this model is not very good.

Let’s try a better model. As a described in a previous post, Silver and Enten are not adjusting for other important demographic variables like age, income, and so on. Due to the limited sample size (I have 44 rows in my data), it’s not realistic to simultaneously estimate many demographic effects. I’ll just include two more variables: median age and percent of population having a high school degree or less.

| Variable | Estimate | Std. Err. | p-value |

| (Intercept) | 130.7826 | 23.6031 | <0.00 |

| Date | 6.9082 | 6.3529 | 0.28 |

| Deadline | -5.3206 | 4.4755 | 0.24 |

| Type | 0.3334 | 4.9385 | 0.95 |

| Independents | 0.983 | 2.5311 | 0.7 |

| RaceBlack | -1.1497 | 0.1502 | <0.00 |

| RaceHispanic | -0.8587 | 0.2384 | <0.00 |

| MedianAge | -0.8648 | 0.5918 | 0.15 |

| EduHSorless | -0.7326 | 0.2329 | <0.00 |

Surprise! The Type estimate is now only 0.33, meaning if you also do a slight adjustment for age and education Sanders only benefits by 0.33% in states having a caucus. The Deadline estimate is still roughly the same. The fact that the Deadline estimate is stable to this change in the model gives me more confidence that its effect is real. If I include another variable, InternetAccess–an estimate of what percent of the population has access to high speed internet–the Deadline estimate becomes -4.87 and Type is -0.25, consistent. If I also include some regional indicators for the South East, North East, and West (leaving the mid-west as part of the intercept) Deadline becomes -5.74 and Type becomes 0.55–meaning Sanders now actually benefits from primaries relative to caucuses.

The data and code for this analysis is available in this Github repo in the files DemPrimaryData.csv and Rigged.R

It’s the voter registration deadlines, stupid

I shouldn’t be writing any of this. I’m supposed to be finishing my thesis right now. So I’m not going to spend the time to find data for primary turnout this year and do a regression to show that turnout is depressed by early registration deadlines. Instead, I will cite several facts which are either obvious or easy to verify with Google.

- Young people are more likely to be first time voters.

- Young people and first time voters are less likely to be registered, and if they are registered they are more likely to be registered as Independents.

- Young people and first time voters are less likely to know that registration deadlines exist and can be surprisingly early.

- Some states with closed primaries, like New York, have even earlier deadlines for party affiliation changes. New York’s was back in October of 2015, four days before the first Democratic debate. New York’s turnout was also second lowest of any state…

Nate Silver and Harry Enten ignored all of this. They conducted a highly flawed statistical analysis that left out important demographic controls and had no data at all related to registration deadlines or other forms of voter suppression. Enten in particular with his background in political science should know there is a vast literature of research on voter suppression involving things like registration deadlines and voter ID requirements. By pretending that the caucus effect is the only one that matters, they claim to answer a far bigger and far more important question than they actually do, and the answer they give for their limited question is still flawed.

Bernie might have been winning…

My own analysis, controlling for more demographic variables and checking that my results are stable when I add or remove several of these controls, shows that Sanders probably lost at least 5% on average in states that did not allow same-day registration. Sanders currently has about 45% of the delegates. It’s impossible to say anything counter-factual about this with certainty, but try to imagine how different things would be. The first Super Tuesday would have been far less devastating, and we may never have seen the widespread media narrative that developed about Clinton’s commanding lead in “delegate math.” The following states might have switched from a loss/tie to a tie/victory.

| State | Advanced days | Vote % Bernie |

| North Carolina | 23 | 40.76 |

| Arizona | 28 | 41.39 |

| NewYork | 23 | 42.01 |

| Ohio | 27 | 43.13 |

| Pennsylvania | 28 | 43.56 |

| Kentucky | 28 | 46.33 |

| Connecticut | 1 | 46.42 |

| Illinois | 27 | 48.61 |

| Massachusetts | 19 | 48.69 |

| Missouri | 26 | 49.36 |

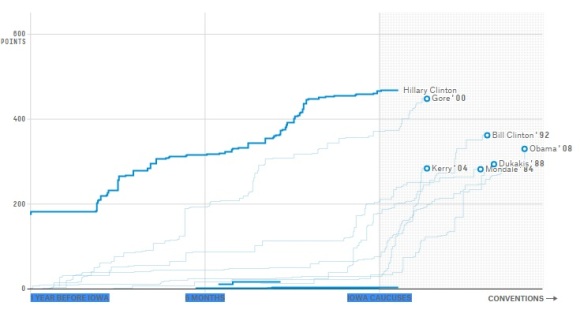

Conservatively, Bernie might have won 4 or 5 more states, and might have come close to a tie in New York. The clear change-point in this graph might not have happened:

I think it’s safe to say that the lack of same-day registration is a very significant factor in Clinton’s lead. In all of this, I did not even begin to ask how it might have been different if closed primaries were open to independents.